Visiting Japan

People like to ask me what they're supposed to do in Japan.

I grew up in Asia, and my mother is Japanese; because of this, I visited Japan several times a year for most of my childhood. And now more than ever, every year many of my friends go to Japan for honeymoons, vacations and other fun. Hence the query. People think I know what I'm doing.

It's a hard question to answer. It's like asking, “I'm going to America for a week. Where should I go?”

Most people visit Japan by going to Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. This is like visiting the US by going to San Francisco, New York, and DC.

You sure did go on a trip. You definitely went to America.

But did you go to Disneyland? Did you explore the swamps of the Everglades? Did you stare in awe at the depths of the gorges of Arizona? Did you drive down Sand Hill Road in Palo Alto and appreciate how this quiet street has generated trillions of dollars of economic growth – or even better, meet the people who made it happen? Did you go to Fargo or Compton? Do you understand what it means to visit Selma? Did you visit a nice home in the suburbs?

Japan is as complicated a country as the United States: what it doesn’t have in physical expanse, it makes up for in a longer history. Don’t get me wrong - I'm not saying you should go to Shimonoseki or Sekigahara on your first trip to Japan. But I think you can do better than the Empire State Building and the Painted Ladies.

Any travel guide to Japan will necessarily fall short. But here are eight pieces of advice I can give:

1. Go to an onsen

Onsen are Japanese baths; they’re split by gender. You show up, you take off all your clothes, you wash in a shower cubby (Very important! Don't skip this!), and you get into a large, steaming hot, communal bath.

Visitors always get squicked out by the nudity, which I find tragic. As a young girl, I’d go to the onsen with my mother, and it was healthy for me to see the wide range of female bodies: the old women with saggy breasts, the nubile young women, the middle-aged mothers with caesarean scars. As a child, I didn't care; as an adult, I've made my peace with it. Teenagers tend to be most self-conscious, though they're also the ones who would benefit the most!

Onsen are incredible and easily the thing I miss most about Japan when I'm abroad.

The baths themselves are pleasant, and designed to be beautiful. If you're outdoors, you can close your eyes in contemplation. If you’re in the right sentō, you might hear the neighbourhood women gossiping about local drama. The fanciest onsen are almost like theme parks, with multiple stories and several baths, each with their own collection of minerals. I often overheat very quickly, so I'll jump into the cold pool to cool down, and then peruse the other baths to decide what I'd like to sample next.

My favourite kind of onsen experience involves a hot bath outside on a snowy day. When you overheat, you can simply sit on the ledge and let the freezing air cool you down. It’s very surreal.

As a kid, I'd go to these onsen theme parks with my family; and after the onsen we would hang out in the lounge in our yukata, playing the silly games where you try to catch a goldfish. My parents would enjoy a drink from the vending machine as we sat in the massage lounge chairs and looked out at the view.

Really, Grant Slatton describes it best in Onsen Unreality:

You leave the baths and stop by one of the food stalls to get some ramen or teriyaki. Drink a crisp Asahi. Lounge around. Stroll outside. Go back in the baths. Come back out, play a carnival game. Eat another snack. Baths again.

Soon enough 6 hours have passed, but you feel like the outside world must have been frozen this whole time. You go back into the locker room, change into your normal clothes, check in your RFID wristband to pay the final bill (totally reasonable amounts, unlike Disney).

Then you walk back out onto the street. It's night. Catch the train back to Tokyo. What just happened? Why did this slightly hokey theme park make such an impact on my life? We may never know.

- Escape the Golden Triangle (with care)

Everybody and their mother will tell you that your first trip to Japan has to be the classic ‘golden triangle’: Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka.

Tokyo is well worth visiting. It’s such a large city that even the sheer mass of tourists can’t change the basic underlying character of the place. One might even call it the Platonic ideal of urbanism; it's not for nothing that a third of all Japanese people live in the Tokyo-Yokohama area. For shopping, culture and food, it can't be beat. Like New York, you could spend a lifetime in the city and still not start to understand it.

Kyoto is also excellent, and it is not an exaggeration to say it has a beautiful old character that you can’t find elsewhere. In World War II, it was spared the worst of the American bombs; when Truman proposed dropping the nuclear bomb on Kyoto, his secretary of war nixed the plans as a crime against humanity.

He was right. But the old parts of Kyoto are also small, and now they are overrun with souvenier shops and mass tourist groups. If you do go, I recommend getting up at sunrise to see the temples and gardens, and renting a bike to get out to the north of the city, away from Gion. And don’t go in the summer; it’s an oven.

Osaka is a lovely city with much to recommend it – if you speak Japanese. If you don’t, it is a second-rate Tokyo. I would recommend visiting a small Japanese onsen town instead, or perhaps even Morioka? Or you could go out to a suburb of Kobe or Hakodate, somewhere where you can sit in an empty kissaten and chat with the owners, and while you listen to good jazz and examine the collection of vintage antiques that they’ve picked up over the years. Kissa culture is made up of people who simply want happy lives; the decades of the 70s and 80s represented by them is as Japanese as the lantern-lit streets of Gion.

If you like jazz, old cafes and getting off the beaten track, I recommend reading the travel writing of Craig Mod.

3. Eat cheaply

Japan truly is a wonderful place where you can eat high-quality food for almost nothing. Given the choice between a $30 sushi meal in Tokyo and a $150 sushi meal in San Francisco, I will always take the former.

It has tourist traps. The worst meal I’ve ever eaten in Japan was in Gion, and it was the most expensive, too. The menu was in English - always a bad sign.

Here is some standard advice you can find on the internet: Japanese restaurant review standards are much lower than the US; a restaurant rated 3.5 is excellent and one rated 4.0 should be considered michelin-star quality. Anything ranked 4.5 and above on Google Maps is populated entirely by tourists, and should be avoided.

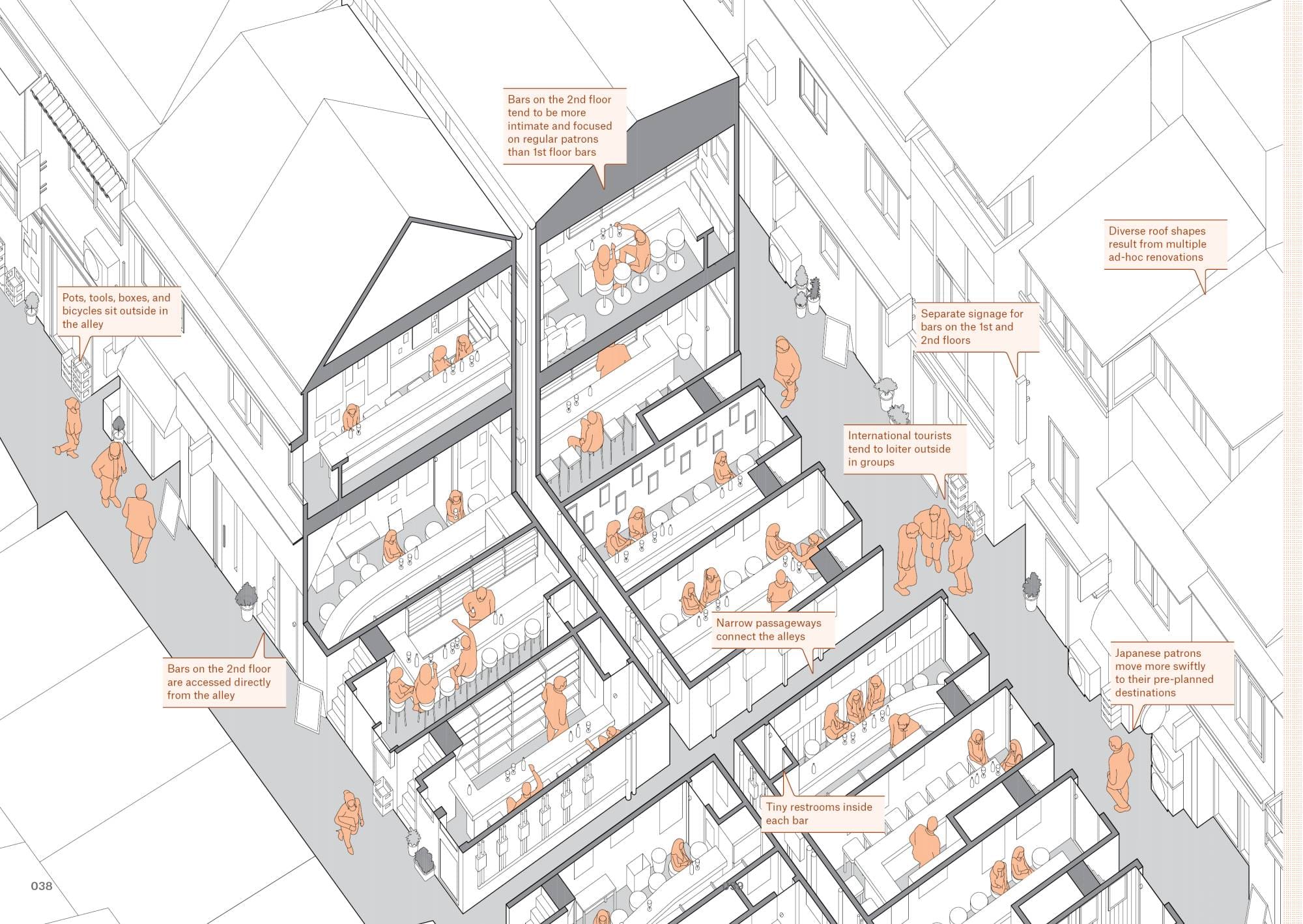

My advice is to leave your hotel, wander two or three random blocks away, and walk into a restaurant that doesn’t have English on the menu, where the meals are less than 2000 yen per person. Remember to look up, too; many restaurants are placed on the second or third floor of a building. You can use Google Translate’s camera feature to translate a photo of the menu when it's time to order. Chances are, the restaurant also has one English-language copy of the menu which they’ll hastily fetch for you when you enter.

Consider visiting chain restaurants; they are all surprisingly excellent. Japan is not really a place where you need to plan your food in advance (unless you’re vegetarian); your odds of rolling well at the median restaurant are very high.

4. Eat expensively, with care

One thing to remember about the best parts of Japan is that they aren’t made for you, especially if you can’t speak Japanese.

The small restaurants with eight seats that don’t take reservations? The restaurant owner expects his usual set of regulars to rotate in, and he spends the evening chatting with them. So if you and your four friends roll in and speak English all evening and treat him like a service worker – well, why would he ever have you back?

Most of these places will simply turn away foreigners as a result. (It's not personal - the wrong type of Japanese people are also not invited - but they have the social sixth sense to tell when they aren’t welcome, so the issue never comes up.)

And yet, some of these places do serve food that is out of this world. So what are you to do?

One of the best ways to eat expensive and good food in Japan, is to ask your hotel concierge to help you book restaurants. (This assumes you are staying at a very fancy hotel, like the Palace Hotel or the Four Seasons.) The hotel concierge is your social guide; they know which chefs like serving foreigners, and/or are willing to tolerate some discomfort for the extra money.

And you need a reservation. The best restaurants don’t take walk-ins; the chef goes out to buy food in the morning, and so he needs to know who’s going to show up. The earlier you can book, the better.

Alternatively, services like omakase.in or Tableall can help; they usually fill in cancellations for restaurants, and they also serve to translate between foreign guests and Japanese chefs. This reddit thread is a good place to start if you'd like to learn more.

I always go into nice restaurants in Japan with the attitude that the chef is doing me a favour by serving me, and I recommend you do, too! I will always remember the complaint a sushi chef in Ginza once made to me, saying that the ‘other Americans with the black cards’ were so obnoxious. Don’t be that person!

For the best time, learn Japanese and sit at the bar.

- Read up on the War

Akihabara, or the Electric Town, is many things: nerd paradise, a surprisingly trashy and seedy neighbourhood, a cornucopia of electronic goods, an exemplar of modern Tokyo. What you can't tell, from the neon signs is that it used to be a thriving black market in post-WWII Occupied Japan, when food was so scarce that half of Japan would have starved but for emergency American imports.

If you want a book that will upend your impression of Japan, I recommend Embracing Defeat by John Dower. It's a Pulitzer Prize-winning, detailed account of post-WWII Japan, an empire in occupation and collapse. He tells you about the stories of the homeless people who lived and died in Ueno station; the brutal economy of the under-station black markets; the sultry glamour of the panpan ladies who pleasured American GIs in exchange for a pack of cigarettes or a pair of nylon stockings.

Can you understand Japan without understanding the war? (Everyone knows which war it is, in Japan.) The theme of massive destruction from above runs through so much of the Japanese popular culture, even that which makes it out to us: in Ghibli’s Nausicaa, in Attack on Titan. It was Clara Collier who pointed out to me that is no surprise, given the generational trauma from the firebombing of Tokyo in 1945.

Left: God warriors destroy the world in Nausicaa. Right: A homeless boy starves in Kobe Sannomiya Station just after the end of WWII, in Grave of the Fireflies. I loved Ghibli movies as a kid, but they scared me.

Japan as a nation was stretched to the breaking point, waging World War II at terrible cost to its people: it won't surprise you to learn that Ghibli also portrays the civilian cost beautifully, in Grave of the Fireflies. And for a manga history of how Japan ended up fighting such a foolhardy war in the first place, I recommend Shōwa by Shigeru Mizuki.

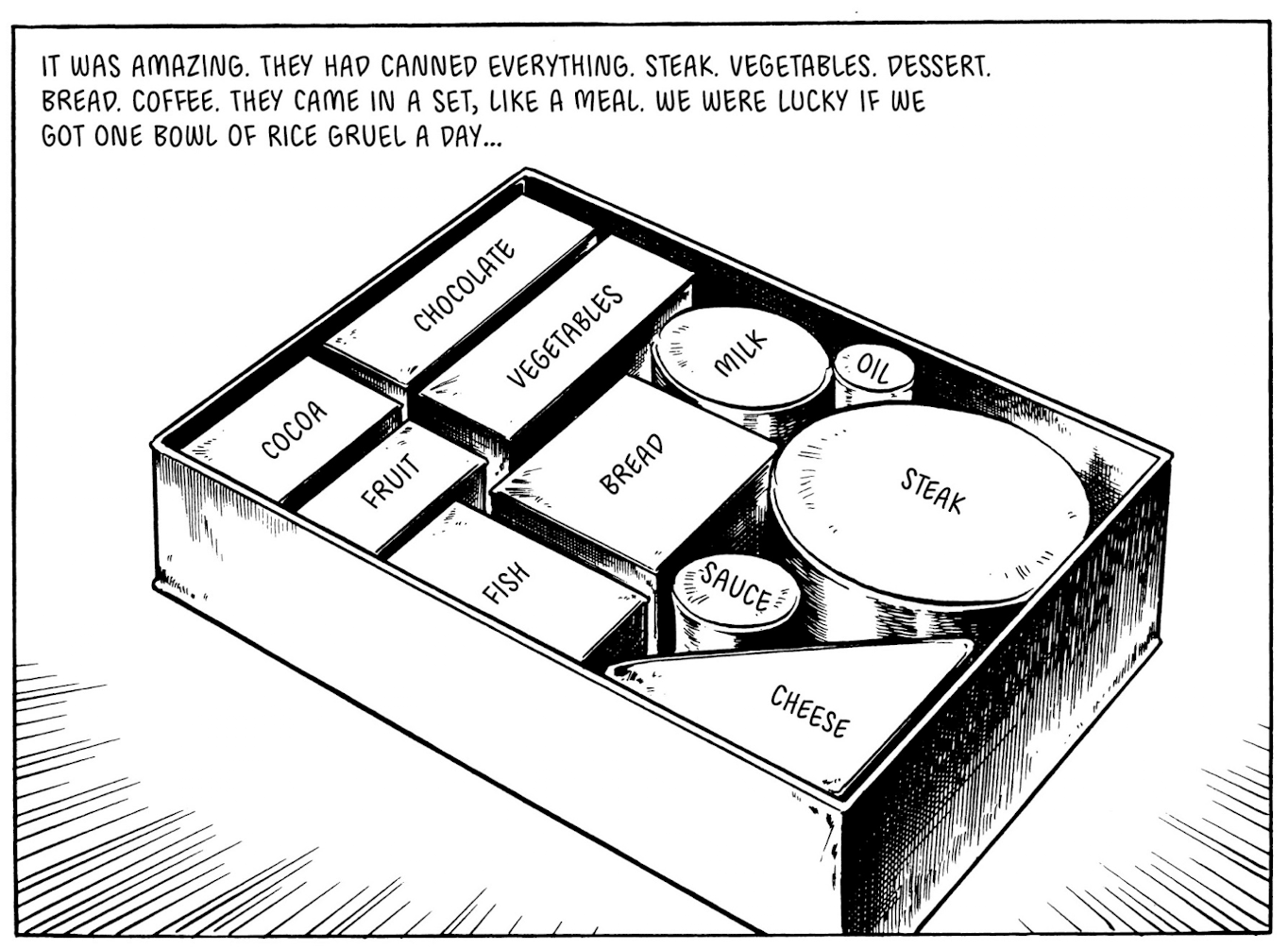

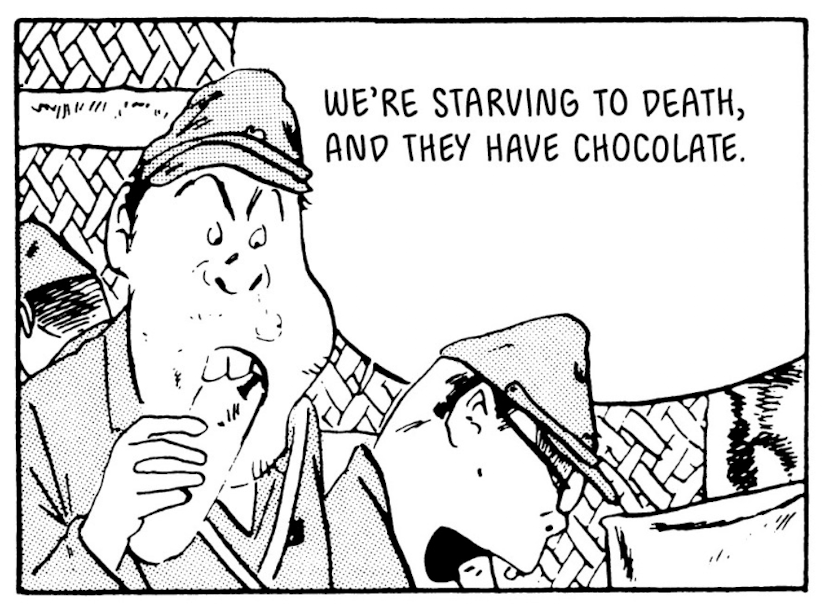

Two starving Japanese soldiers in Papua New Guinea discover the magic of the American supply chain, and realize how doomed the Japanese war effort was. From Showa.

People who visit Japan sometimes wonder if the kindness and hospitality and order is the way things always have been, if it's something deeply genetic or an ingrained culture. No, Japan was poor once too, and that poverty drove the worst of human behaviour. The attitude we see today is hard-won, the result of massive prosperity and economic growth.

6. Walk, walk, and walk some more

Japan is endlessly complicated, and you will only ever scratch the surface on your first trip. People spend their entire lives in the country and never see it all. For all that I love the architecture and history of Japan, and see it where I travel, whenever I go I reflect on how I don’t have a community or friends there; and this makes travelling there a little bit lonely for me.

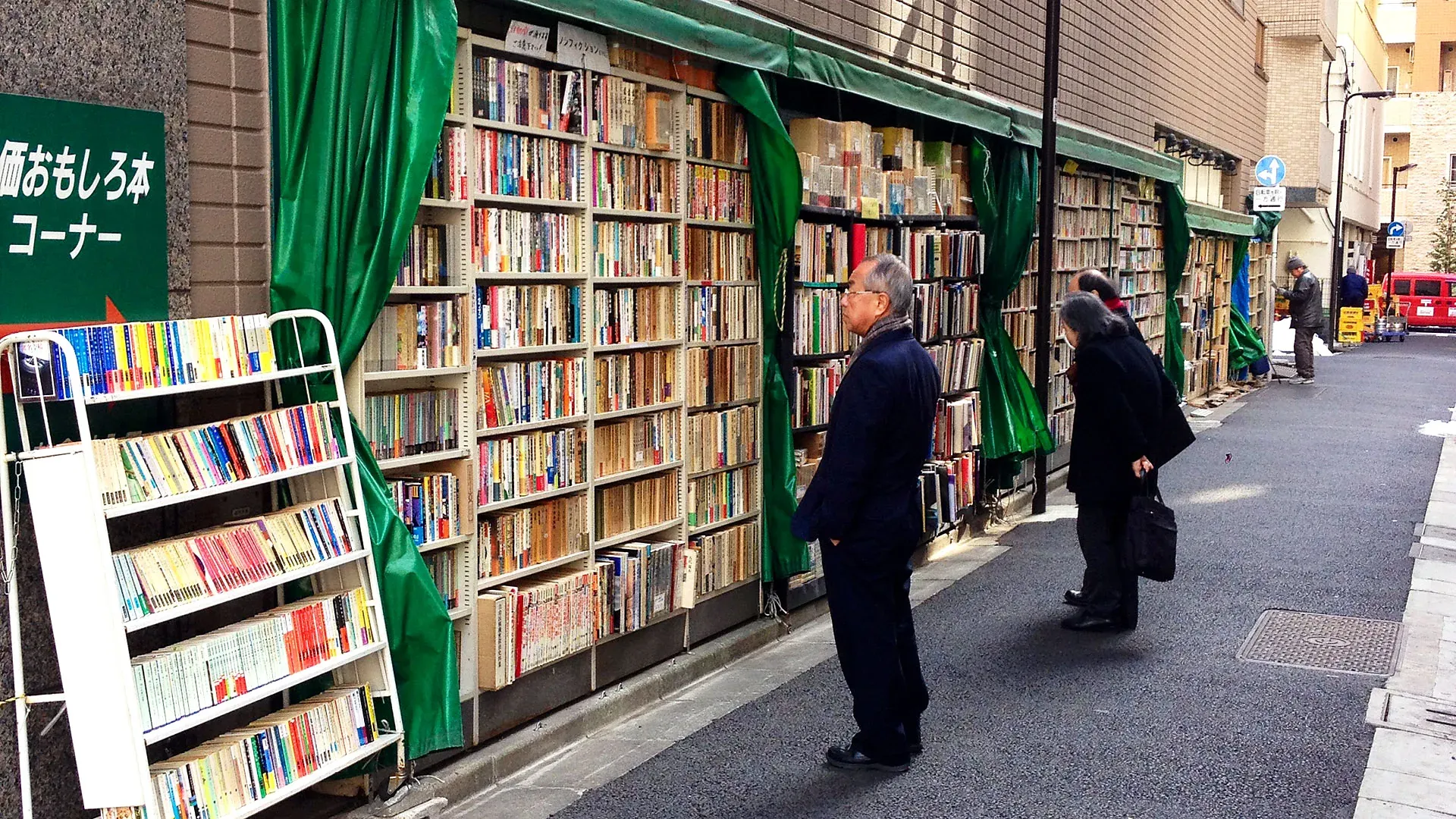

But you can have an excellent time by wandering around and opening yourself up to conversation with the people you run into. You can see so much of the city of Tokyo by picking different neighbourhoods and simply walking around: the book-lined streets of Jimbochō, the glittering flagship stores and sheltered ukiyo-e galleries of Ginza, the commercial malls and three-dimensional street grids of Shibuya and Shinjuku.

When I’m in Japan, I regularly walk 20,000+ steps a day. It’s exhausting. If possible, I recommend ramping up ahead of time, by deliberately walking around your neighbourhood or setting up a walking pad under your desk. While there’s some charm to taking the subway, you can afford to take taxis and Ubers to get around, and you should; you need to ration your steps carefully, so don't waste them!

I always recommend to my friends that they bring a copy of Emergent Tokyo. This is not very kind advice, as the book is incredibly dense and overwhelming. But if you have the time to leaf through it as you explore Tokyo, it gives X-ray vision, explaining what is actually going on in the slightly drab and boxy buildings that you’ll see as you wander through.

7. Learn Katakana

This is by far the most high-effort tip, but learning katakana is how you 80/20 learning Japanese, if you’re an English-speaking foreigner.

What is katakana? At a high level, Japanese writing has 3 parts: hiragana, katakana and kanji. Hiragana is composed of round, simple characters; katakana is composed of sharp, simple characters; and kanji are all the complex characters, In this sentence:

> 冷たいビールを飲みたいな

Which reads, literally, ‘a cold beer, I’d like to drink!’ 冷 is kanji; たい is hiragana; ビール is katakana, and reads 'bi-ru'. Guess what that means.

In practice, kanji is often used for complex concepts, hiragana is often grammatical connective tissue (and some simple terms), and katakana is used for foreign loanwords.

A whole alphabet for foreign loanwords! It seems odd, but makes more sense once you consider that Japanese – like English – is a language that has been overrun by at least two foreign invasions. The first was the introduction of Chinese language and concepts, starting back in the 5th century; the second was the opening of Japan to the West in late 1800s, when Japanese scholars travelled to the west and brought back English and German concepts of politics, law and war.

Some of these are, as a result, non-intuitive; for instance, the Japanese word for ‘part-time job’ is arubaito, from the German ‘arbeit.’ But a helpful thing for you, you English-speaker, is that many food and tourism concepts are often written in katakana, like coffee (コーヒー, or ko-hi), hotel (ホテル, or hoteru) and ice cream (ソフトクリーム, or sofuto kuri-mu). It’s satisfying to puzzle out katakana and play the game of mapping it to English, sound by sound.

There are 52 phonetic characters, and no capital letters; so if you make some flashcards you can study them on the plane on the way over.

- Remember the Bubble

The other big facet of Japanese trauma is 'the bubble'.

You actually see it most outside of Tokyo. A classic bubble experience is wandering around a small town and finding some odd, large boondoogle, like an abandoned restaurant with a giant hotdog on it, or a run-down seaside resort.

I once stayed in a lovely youth hostel in Tōno. At night I spent my time speaking with the owner. She reminisced about how much she had travelled in the 80s, when Japan was on the rise and everything was cheap. “Of course, that was all during the bubble. When it popped, everything changed,” she said.

I am not a macro-economist, but from what I understand, Japan wildly overextended itself in the 80s. Banks lent money that had no chance of being repaid; people made investments that had no chance of ever coming to fruition.

A German man in his seventies or eighties runs a restaurant near the Japanese seaside town where my parents spend the summer. Let’s call him Mr. Munich.

Once, my dad asked him why he was still working. Well, during the bubble he had taken out a massive loan to build a large German bierhall. He was proud of it; he showed us a picture of it. It was incredibly kitschy and cute. But when the bubble popped, business stopped, and he couldn’t pay the loan back.

In America, he would have wiped the slate clean. It would have been painful, and his creditors would have had to realize a loss, but they would have moved on. But the Japanese banks never realized those losses on their balance sheet. Instead, his bank asks him, now, to pay a small fraction of the loan back; and as a result, he still works to bring in the income to pay it off, in this comical facsimile of an economy.

You can run your economic policy this way, but it's a mistake. For two decades, it meant that the country's resources went into helping the old, and there were no jobs or opportunities for young Japanese people. There were a generation of broken dreams, and we see it today in how there are few new industries or technological breakthroughs coming out of Japan - or, indeed, talented young people. Perhaps it's for this reason that the government is keenly pushing tourism... and, well, I suppose that's why we're here!

If you find me helpful, please let me know! Don't take this all too prescriptively; the most important thing is to find what you want to find in Japan. It's an amazing place for serendipity to strike, if you open yourself up to it. It's a wonderful place, and I hope you have an incredible time.